The Mystery Woman Who Co-founded Krusteaz in Seattle

Learn the behind the scenes story of how this legendary local company began.

This story originally appeared in the Seattle Times on Feb. 28, 2020. Click here to view the original article by Jackie Varriano, Seattle Times food writer.

“You never know what kind of brilliance can happen over a game of bridge. In 1932, the women of a Seattle bridge club had a simple idea for an easy-to-make pie crust. They called it ‘Crust Ease’ (a clever combination of ‘crust’ and ‘ease’), and little did they know it would lead to a wide variety of home-baked goods enjoyed by everyone around the country.”

That paragraph appears on the Krusteaz website when you click on “Our Story,” and below it is a photograph of four smiling women dressed in period-appropriate clothing, sitting around a table. It appears that these are the bridge-club women whose pie-crust recipe formed the foundation for the Krusteaz line of baking mixes by Continental Mills, a Seattle-area company with products that still dot grocery-store shelves today.

It seemed like a fascinating piece of local food and women’s history.

The fact that four women got together to start a business in the 1930s was significant. After all, the Equal Credit Opportunity Act, which makes it illegal for creditors to discriminate against loan applicants based on gender, race, marital status or national origin, did not pass until 1974. Before that, widowed, single or divorced women had to bring a man along to co-sign on any credit application.

But when I reached out to Krusteaz hoping to tell the story of a local company that was started by women and, 88 years later, is still family-owned and family-operated, I was surprised to find that no one could identify any of the women from the bridge club.

The Heily family has led Continental Mills for three generations, but while they have been involved since 1947, they did not start the company. John J. Heily, the grandfather of current CEO Andy Heily, was the first to become involved with the company, in the mid-1940s. Krusteaz pie crust was Continental Mills’ first product, and it hit grocery shelves in the early 1930s, when Seattle was in the grip of the Great Depression.

As Dana Ross, Continental Mills’ director of communication and community engagement, wrote in an email, Andy’s father, John M. Heily, “was not particularly sentimental about history until the past few years,” and thus the names of the women have been lost over time.

Ross could offer one name, though.

“The husband of one of them was named ‘James Charters,’ ” Ross wrote.

Thus began the quest to find the elusive Mrs. James Charters, co-founder of Continental Mills, upon whose pie-crust recipe the Krusteaz brand was created. Who was the mysterious Mrs. Charters? And why does it seem all information about her been lost to history?

It’s not easy to find histories of “regular” women from the 1930s.

“Abigail Adams hasn’t been erased, but working-class women and women of color tend to be,” says Shirley Yee, a historian and chair of the department of gender, women and sexuality studies at the University of Washington.

One reason why: Until the late 1960s, married women, and even widowed or divorced women, were often publicly referenced by their husband’s names. It wasn’t until the 1970s that some newspapers (for instance, The Washington Post) started regularly referring to married women using their first names.

“Journalists didn’t invent social norms, they tended to follow the social norms of the day,” Yee says.

So even though a deep dive through old Seattle Times archives yielded confirmation that James Charters had a wife, in almost every instance, she was listed as “Mrs. James Charters” or “Mrs. J. M. Charters.”

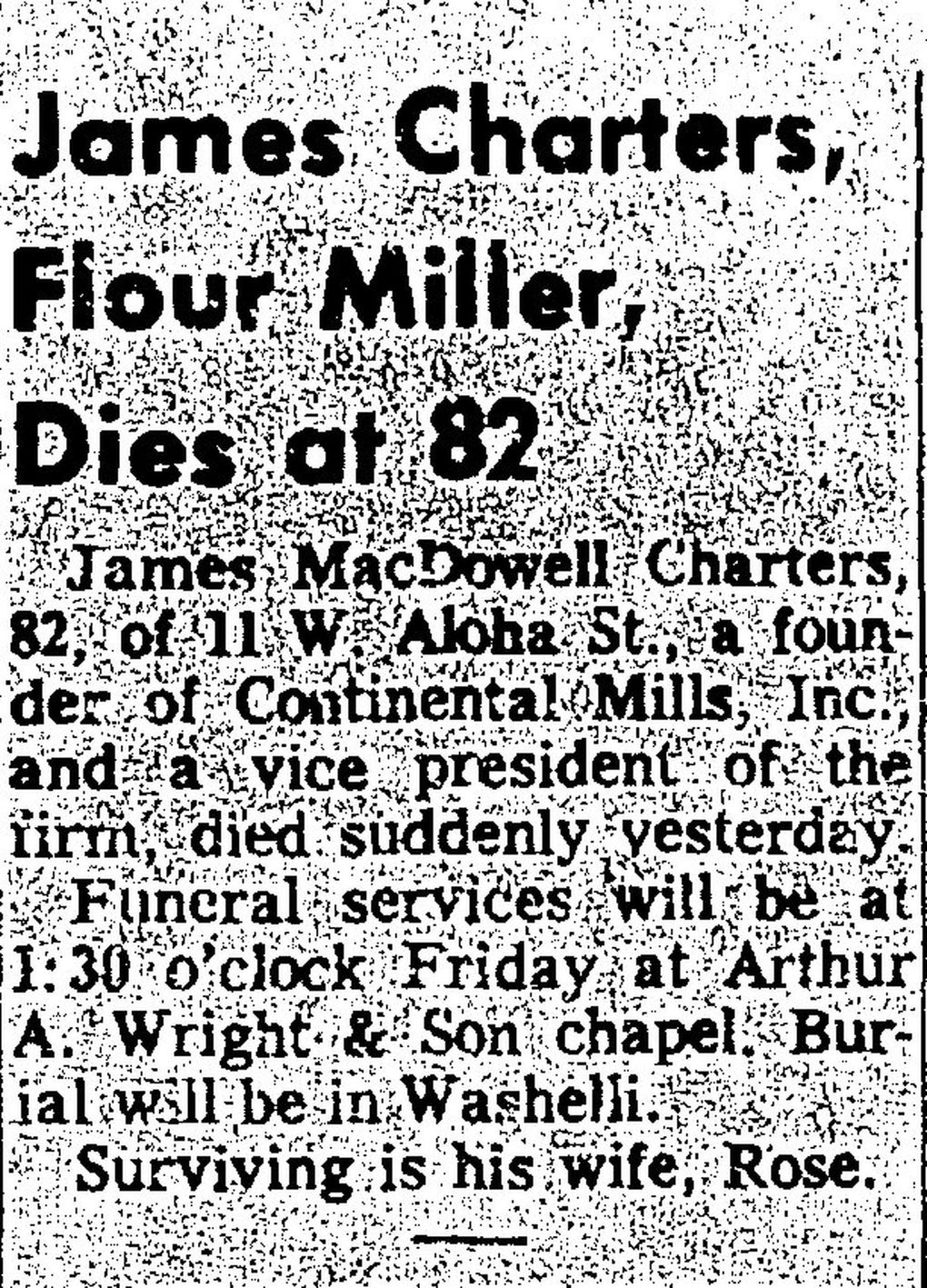

Luckily, James Charters’ obituary in the April 1, 1964 edition of The Seattle Times provided a valuable lead in the search for Mrs. Charters. The very last line read: “Surviving is his wife, Rose.”

James MacDowell Charters died in March 1964, at age 82. His obituary appeared in the April 1, 1964, edition of The Seattle Times, and... (The Seattle Times archive) More

Finding Rose’s first name led to her maiden name — she was born Rose Gilbreath — and that, in turn, yielded a trove of information. (And some misinformation. Record-keeping in the 19th and early 20th centuries can’t match the internet era — for instance, the Times obituary following Rose’s death in 1970 misreported her age; she was 94, not 87.)

So who was Rose Gilbreath Charters?

The woman who co-founded Krusteaz came from one of Washington state’s pioneering families. Her father, Samuel Love Gilbreath, journeyed to the Oregon Territory by wagon train in 1852, and subsequently became the first white resident — and later, the first sheriff — of Washington Territory’s Columbia County.

Rose Charters was born Ada Rose Gilbreath in 1876 on a farm in Dayton. She was the ninth of 13 children and she attended Washington State University back when it was known as Washington Agricultural College. She became a schoolteacher in Walla Walla, but had moved to King County by the time she married Chicago native James MacDowell Charters in 1918.

State public records filled in more blanks about the Charterses and Continental Mills. Rose would have been 56 years old when the company was founded in fall 1932, at which time it also started using the word “Krusteaz” as the brand for its packaged pie-crust mix. Rose Charters was listed as a vice president on annual reports until May 1969. In June 1970, the summer before her death, a new name appeared under President John J. Heily: Vice President John M. Heily.

Andy Heily, who would eventually take the reins from his father John M., didn’t know much about the bridge club or the attached origin story, but he offered up his aunt, Timmie Hollomon, as a resource.

Hollomon, 83, is John M. Heily’s sister. She remembers going to work at the Continental Mills factory with her father and her best friend, Peggy, on rainy summer days.

“It was just Mr. and Mrs. Charters and they hired people from the neighborhood to run the lines,” Hollomon said when reached by phone and asked what she knew about the founders of Continental Mills.

Rose Charters created her pie-crust mix at an opportune time. In the Depression era of the early 1930s, unemployment lines were long, money was tight and while grocery stores had started carrying some premade baking mixes, all these products still required the cook at home to add ingredients like butter, milk, oil or eggs. A mix that only needed water was quite the revelation.

1 of 5 | Continental Mills was featured in a story in the Jan. 13, 1963, edition of The Seattle Times. The story references “Mrs Charters” but... (The Seattle Times archive) More

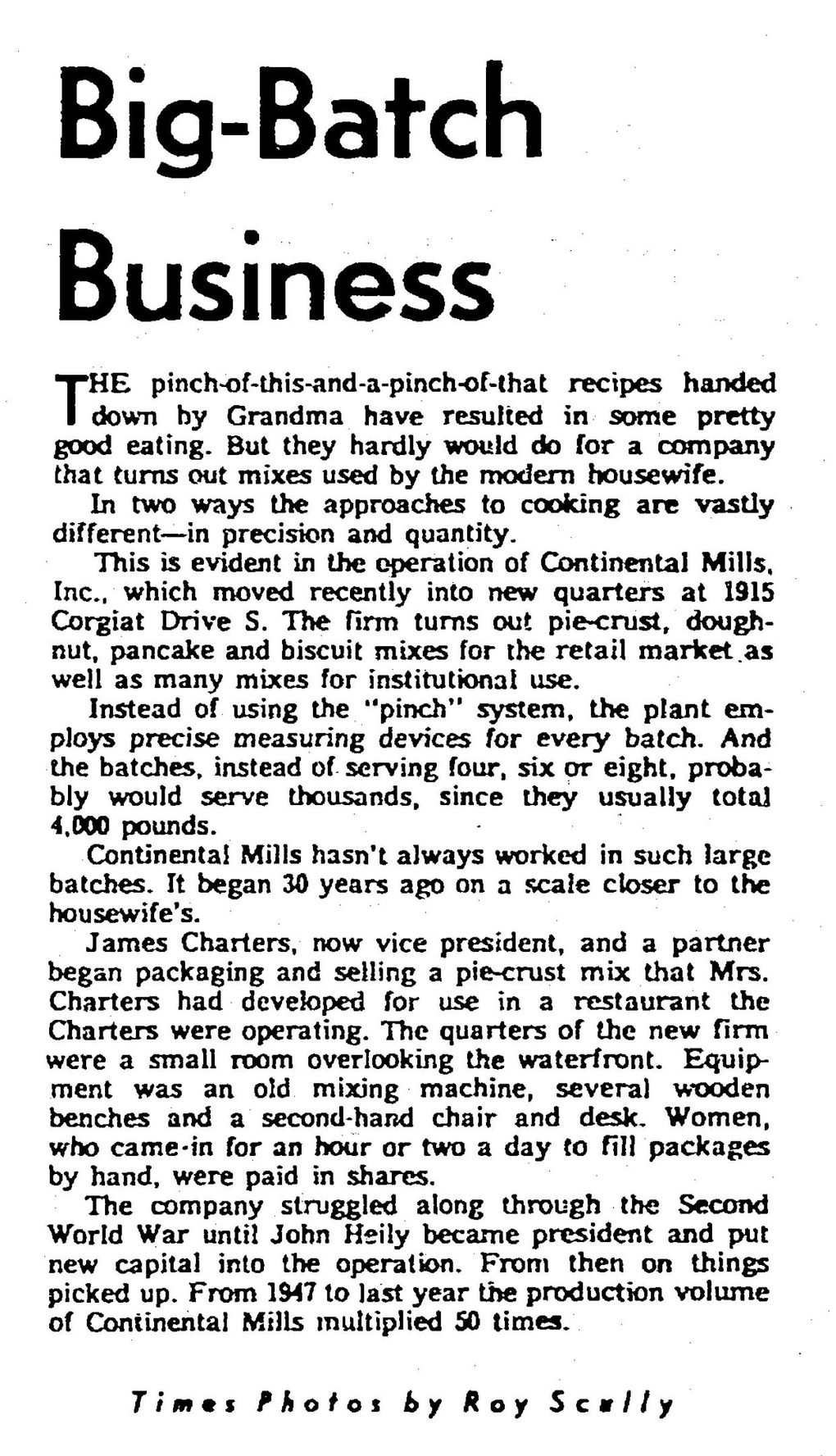

As Hollomon remembers it, Rose started selling the pie-crust mix to friends, neighbors and local cafes. Demand quickly outgrew the Charterses’ kitchen. James found a small manufacturing plant, and with a loan from investors in his hometown of Chicago, the Charterses and a handful of employees opened shop.

No one knows whether the bridge club ever existed. Rose Charters was, indeed, a member of a social club called the Radiant Chapter, Order of the Eastern Star, whose members occasionally gathered to play cards — but whether this was the “bridge club” of the Krusteaz origin story, we’ll never know. Any concrete evidence seems entirely lost in history. Also, the photo of the four women on the Krusteaz website isn’t authentic; it’s a re-creation of the “four women from a Seattle bridge club” narrative, shot by employees for an internal promotion in the ‘90s.

In the 1940s, John J. Heily joined Continental Mills at the request of his brother-in-law, one of the Charterses’ Chicago-based investors, who had asked the first Heily to help turn a sagging small business around.

From that point on, the Continental Mills story becomes about the Heilys, who, thanks to shrewd business decisions made over three generations, turned a struggling business into the successful baking-mix enterprise that still thrives today.

Early in his tenure, John J. Heily hired a food chemist who helped expand the company’s product line to include cake, doughnut and biscuit mixes. Another big bump came with the introduction of the Krusteaz just-add-water buttermilk pancake mix, developed in partnership with UW’s home economics department in the late 1940s.

In 1975, in a move that changed the company’s trajectory, John M. Heily beat out Pillsbury to win the contract for the kitchens that fed workers building the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System. This lucrative deal prompted the company to scale up operations, which helped when Continental Mills got its products into Costco a few years later.

Today, Tukwila-based Continental Mills still prides itself on being a family-owned and family-oriented company that has hewed close to its local roots. Many of the company’s 800 employees have been there 20 years or longer.

As a kid, Andy Heily spent his summers at Continental Mills, painting the warehouse or sorting mail. He joined the company working full time after graduating from business school and worked closely with his father over the next 18 years, up until John M. Heily’s death last September. Andy Heily took over in 2015.

1 of 2 | Gil Hernandez, packaging operator at Continental Mills in Kent, sets up equipment on the Krusteaz lemon-bar assembly line at the Krusteaz manufacturing plant in Kent last... (Ellen M. Banner / The Seattle Times) More

John M. Heily’s spirit very much lives on within the walls of the company that he kept alive through the decades. One of his mantras was “Fierce Pride,” and those words pop up all over the Continental Mills headquarters.

“He was such a cultural leader for the company and just the patriarch of the company,” Andy Heily said of his father. “There’s all sorts of constant reminders of him.”

Like his father and grandfather did before him, Andy Heily has also spearheaded some innovative changes with the company’s longevity in mind. The company stepped away from several of its brands to concentrate on improving the Krusteaz line and has since introduced protein-fortified mixes and mixes that use sustainably farmed wheat.

Continental Mills was surprised to hear about Rose Charters and her role in the company’s founding. After all, James Charters died back in 1964, and Rose Charters followed in 1970. Prior to Rose’s death, the Charterses’ shares of the company were sold to the Heilys. We can only speculate as to why her contributions have been lost to history. Perhaps because the Charterses never had any children to advocate on their behalf? The same goes for the bridge-club origin story. Maybe four women who worked there early on were conflated into the “four women at bridge club founders” story through an innocent game of telephone? Or maybe Rose talked to friends about the recipe before she and James started selling it?

The Heilys grew Continental Mills from a small regional business into the flourishing national company it is today. But Rose Charters — a Seattle school teacher, not a food scientist or a chemist — created the first product. She was the first to bring it to market.

And even though Rose Charters’ name has been forgotten over time, a reminder of her legacy remains deep in the Continental Mills product line. It doesn’t even crack the top 100 best-selling items Continental Mills makes, but Krusteaz still carries a pie-crust mix for sale — albeit mostly in the Pacific Northwest.

“If it wasn’t part of our heritage, we’d probably discontinue it,” Andy says. “But who’s going to be that person? Not me.”

Krusteaz/Continental Mills Timeline

- 1876: On Sept. 20, Ada “Rose” Gilbreath is born in Dayton, Columbia County — in what is still known as “Washington Territory.”

- 1882: James MacDowell Charters is born in Chicago, Illinois.

- 1918: James Charters and Rose Gilbreath get married in King County.

- 1932: In June, James and Rose Charters start making and selling Krusteaz brand pie-crust mix. Continental Mills was incorporated as a company in Washington state on Oct. 1, 1932. James Charters, August Fritsche and J.R. Cissna are listed as its first trustees.

- 1941: A Seattle Times article reports the company sold “in excess” of 1 million packages of Krusteaz pastry flour over its first eight years, which averages out to 125,000 packages per year.

- 1945: At the behest of Tom O’Bryan, his Chicago-based brother-in-law, John J. Heily was asked to sit on the board of Continental Mills. O’Bryan was one of the original investors in the company, but hadn’t been in contact with James Charters and needed someone to look in on his investment.

- 1947: Heily is named president of Continental Mills. During his tenure, the company added to their product line, developing recipes for biscuits, doughnuts and a just-add-water buttermilk pancake mix — originally formulated at the University of Washington’s home economics department.

- 1963: Continental Mills moves from its first manufacturing plant in the Central District to one on Corgiat Drive, by what is now Boeing Field. According to a Seattle Times story on Jan. 13, 1963, their first plant included “an old mixing machine, several wooden benches and a second-hand chair and desk. Women who came in for an hour or two a day to fill packages by hand were paid in shares.” The article stated the company “struggled along through the Second World War” until Heily became president. “From 1947 to last year, the production volume of Continental Mills multiplied 50 times,” the Seattle Times' story reported.

- 1964: In March, James Charters dies.

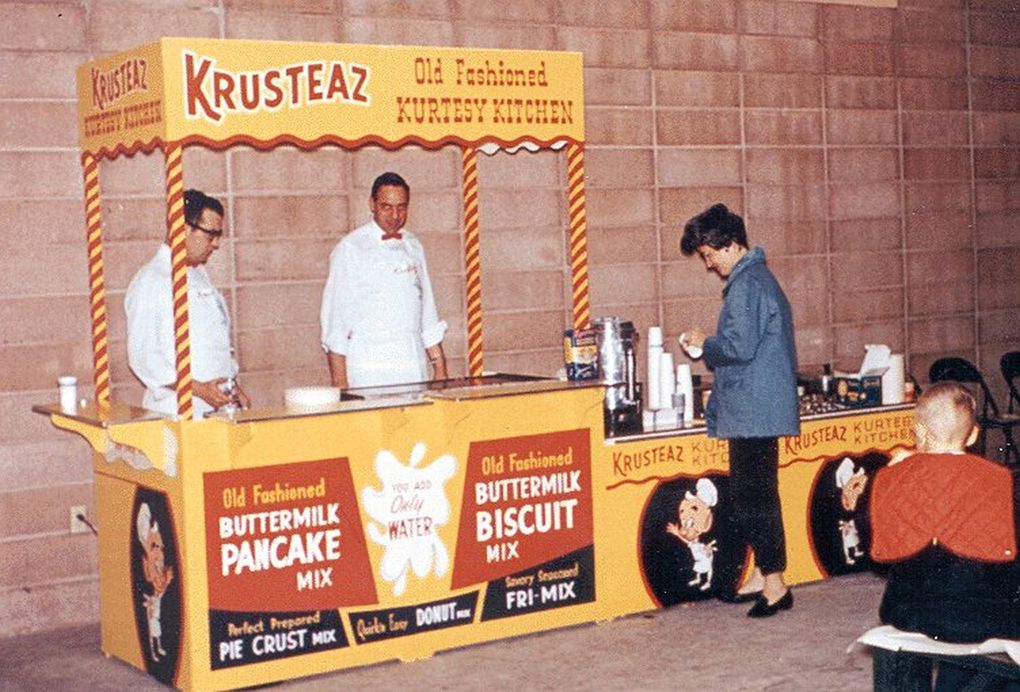

- 1970: Continental Mills salesmen start driving a Volkswagen van kitted out with a griddle, dubbed the Krusteaz Kurtesy Kitchen, to Seattle-area grocery stores, serving pancakes to customers in order to get them excited to try Krusteaz buttermilk pancake mix.

- 1970: On Sept. 4, 1970, Rose Charters dies.

- 1975: John M. Heily takes over from his father, John J. Heily, as president and CEO. That year, he also secured the bid to supply kitchens for the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System, forcing Continental Mills to find new recipes, restructure operations and increase scale drastically.

- 1980: In another breakthrough, Continental Mills starts selling its products at Costco.

- 1999: To increase distribution to a national level, Continental Mills builds a second manufacturing plant, this time in Hopkinsville, Kentucky.

- 2015: Andy Heily takes over from his father, John M. Heily, as president and CEO. He oversees roughly 800 employees across three states, including the corporate offices in Tukwila and manufacturing plants in Kent; Effingham, Illinois; Hopkinsville, Kentucky; and Manhattan, Kansas. Continental Mills now produces enough pancake mix per year to make 2.6 billion pancakes annually.