A Nisei Garden of Memories in SeaTac, and a Soldier's Blood Spilled in WWII

Every Thursday morning, an elderly couple spends a few hours weeding and tidying up the Seike Japanese Garden in SeaTac.

It means a lot to Hal Seike, 90, the last surviving of three brothers. The garden is dedicated to his brother, Toll, a Nisei killed at age 21 in World War II.

At age 90, he’s the last remaining of the three Seike brothers.

Every Thursday morning, Hal Seike and his wife, Fran, 87, make the 1-mile drive from their home to the Highline SeaTac Botanical Garden. It might seem unusual to have a botanical garden beneath a constant stream of jet takeoffs and landings, but there it is.

At their age, they’re still relatively nimble, able to drive and able to spend three or so hours once a week pulling weeds and raking leaves. They’ve been married 61 years.

Each time they visit, they walk past a large wooden board marking the “Seike Japanese Garden,” which occupies maybe an acre of the botanical site.

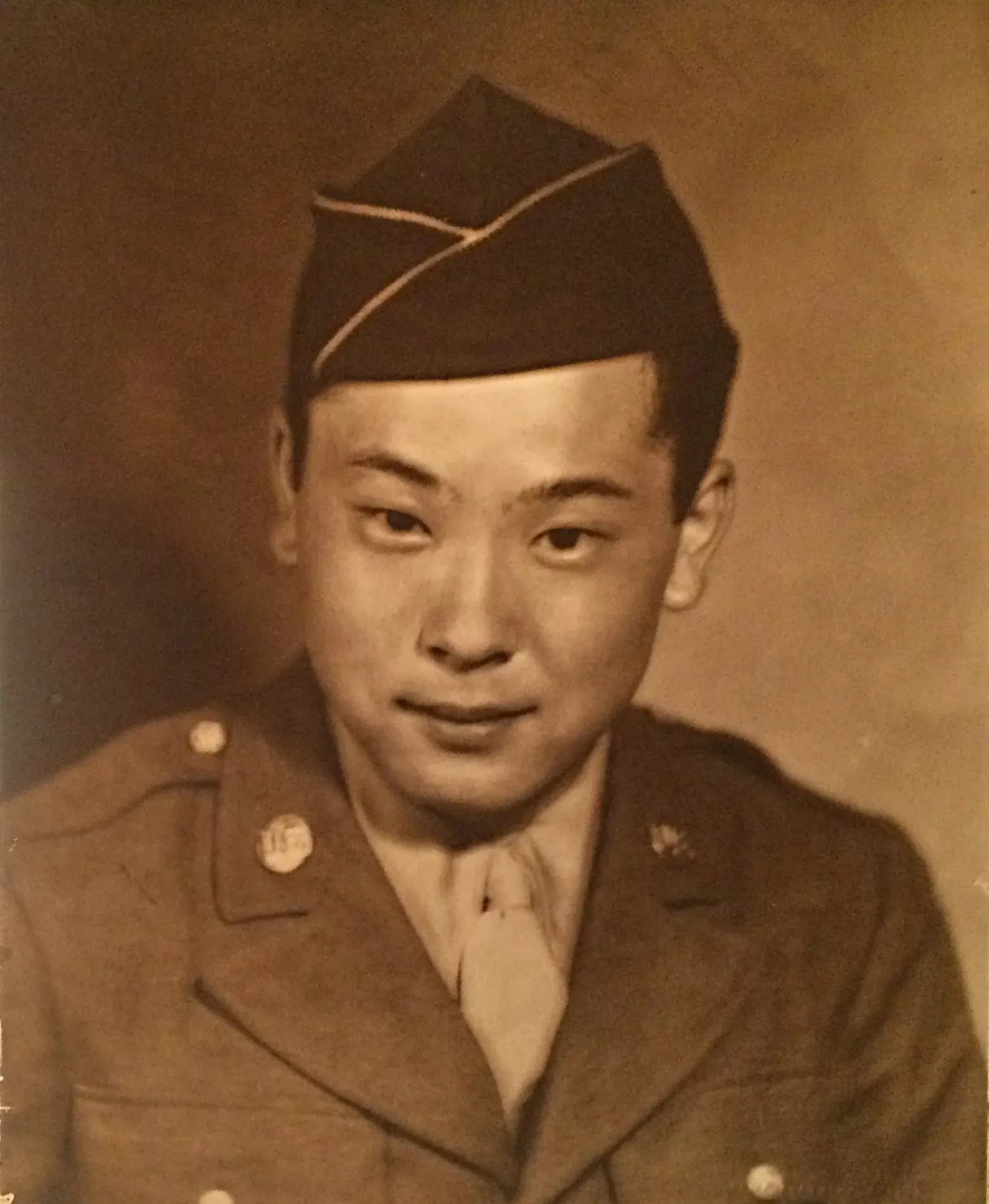

Prominent on that board is a black-and-white photo of a young Army soldier. That’s Toll Seike, the middle of the three brothers. They were all Nisei, meaning U.S.-born children of Japanese immigrants. The garden is a tribute to him.

Toll was 21 when he was killed Oct. 29, 1944, in a horrific battle near Bruyères, France.

Kiyoshi “Hal” Seike and his wife, Fukuye “Fran” Seike, stand in their Japanese garden in SeaTac, where they still work a few hours every Thursday. The Seike Japanese Garden was commissioned by Hal’s father, an immigrant, partly as a tribute to his son Toll. (Ellen M. Banner/The Seattle Times)

In history books it is known as the “Rescue of the Lost Battalion.” While most Americans likely have never heard of it, a Department of Defense article calls it “one of the great ground battles of World War II.”

Says Hal about the garden: “We go there rain or shine, drenched to the bone. I’ve been out there in the snow. I’m really kind of sentimental about it. That’s my family name on it.”

A garden has to be tended, especially a Japanese garden, an enchanting creation of specially placed rocks, a pond with a bridge, Japanese maples, sculptured black pines and a variety of shrubbery.

Upkeep of the entire botanical garden, owned by a nonprofit foundation, is done by volunteers, and they’re scarce.

Battlefield heroism

Toll Seike was a private in the 442nd Infantry Regimental Combat Team, composed almost entirely of Japanese Americans, that during the war totaled 18,000 men.

Its motto was “Go For Broke,” derived from gambler slang used in Hawaii for when a player was risking it all in one effort to win big.

The 442nd compiled an astonishing combat record for bravery — among its many recognitions were 21 Medals of Honor, the country’s highest military award, and 9,486 Purple Hearts.

In the Lost Battalion rescue, the regiment lost 400 men fighting to rescue some 230 besieged members of the Texas National Guard trapped by the Germans.

The fight was “in dense woods, heavy fog and freezing temperatures,” says the Department of Defense article.

The rescuers suffered mass casualties, it says, quoting Army historians. “Then, something happened in the 442nd. By ones and twos, almost spontaneously and without orders, the men got to their feet and, with a kind of universal anger, moved toward the enemy position. Bitter hand-to-hand combat ensued as the Americans fought from one fortified position to the next. Finally, the enemy broke in disorder.”

Hal remembers a letter that Toll send from the battlefield.

“He was really scared and frightened, wet and cold. The German artillery was shooting over his company, and the trees would just shatter, and splatter and crash,” says Hal.

Name in the newspaper

Toll was an American kid. He got his unusual first name because a clerk who was writing down his name didn’t understand the elder Seike’s broken English. He was saying, “Toru.”

Toll shows up in The Seattle Times archives a couple of times.

In 1932, when he’d have been about 11, he is listed as being among “ambitious boys and girls (who) gather at Times Annex to build structures of Old English design.”

It’s not clear why the paper promoted building a miniature village, but it attracted a lot of participants. These days, that’s called “reader engagement.”

In 1941, at about age 18, Toll was among the leaders in the Guest Guesser contest for predicting college football outcomes. Back then, the paper ran a voluminous list of the best guessers so they could clip and save it in their scrapbooks.

Starting the next year, more than 110,000 Americans of Japanese descent on the West Coast would end up in internment camps.

Most of the Seike family were among those trucked away — the parents, along with Hal and his two sisters, Ruth and Shizu, who were all still in school in Highline.

In 1942 the family had six weeks to get ready for the forced relocation. Hal remembers the family holding a garage sale to get rid of household goods.

“It was a Sunday, Mother’s Day, when I remember the big Army trucks came and picked us up. It was kind of a sad day,” Hal says.

Toll and Ben, the oldest of the brothers, were studying at Washington State University in Pullman, which was considered too isolated and so wasn’t in the “exclusion zone” for Japanese Americans.

Toll volunteered for the 442nd.

Ben also would enlist in the Army and end up as an interpreter in the Philippines with the Military Intelligence Service. The Seike kids had only a rudimentary knowledge of Japanese, so the Army sent Ben to Japanese language school. He died in 2014 at age 93.

By the time Hal reached an age to be drafted, the Korean War was on. He ended up doing payroll in the Army.

By then the Seike family had spent more than three years moving among camps in California, until finally the elder Seike was able to work in Chicago at a school-supply company, a place deemed far enough away from the West Coast.

Hal doesn’t talk much about those years.

“It’s something of a sore point,” he says in his understated way. He adds, “We were like prisoners.”

Immigrant with a plan

Shinichi Seike, the father, who died in 1983 at age 95, had come to the U.S. when he was 31. It was the quintessential immigrant story.

He owned a store on Maynard Street in the Chinatown International District, bringing in goods from Japan. He’d make regular treks in a food truck loaded with rice, soy sauce and other Asian goods to Japanese farmer camps in Eastern Washington.

By age 41, Seike had bought 13 acres in what’s now the city of SeaTac. He had a house built.

“We had chickens, one cow for milk, a lot of fruit trees and vegetables,” says Hal.

The elder Seike’s plan was for Hal and Ben to start a plant nursery on the acreage, and so they would study horticulture at WSU.

The father also made sure he wouldn’t lose his property, as happened with other interned Japanese Americans. In the six weeks before being trucked away, says Hal, “My dad had an attorney take care of the legal matters. He was a smart man.”

The family home would be rented out and that income would pay the mortgage on the house and the property taxes. A German-American couple rented the home and took good care of it — “perhaps there were sympathetic” because they also had experienced the wary stares, says Hal.

In 1953, eight years after the family returned from being relocated, Des Moines Way Nursery opened.

It was run by the two remaining brothers.

But the dad had wanted something else on that property. In 1961, he brought in a designer from the old country and had a Japanese garden constructed.

It would be a showcase for the nursery, a showcase for all of the Seike family accomplishments.

And it would honor the son who had been killed in that horrific battle.

The Des Moines Way Nursery lasted for half a century, closing in 2002. The property was bought by the Port of Seattle for its third-runway expansion.

The family home was leveled, but there was something on those 13 acres that was very important to the Seike family.

It was the Japanese garden the dad had constructed.

A photo in the Wing Luke Museum archives shows the dad being given the U.S. flag at Toll’s military service at the Veterans Memorial Cemetery by Evergreen Washelli. His obituary notes that the dad had been a president of the Gold Star Parents Association, for those who lost a family member in the service.

Says Fran Seike about her father-in-law, “He was very emotional when it came to losing Toll. He liked to go to the garden and contemplate.”

It took some doing, but in 2006 a good portion of the Seike Japanese Garden ended up being literally lifted and moved to its current location.

The state Legislature came up with a $246,000 grant. Another $50,000 came from the city of SeaTac.

“Some of those rocks are a couple of tons,” says Kit Ledbetter, SeaTac’s now-retired parks director. “It was important how the rocks were laid out.”

Now, on Thursday mornings, if you happen to visit the garden and you see the elderly couple tidying it up, you know why.

Seventy-three years ago, blood was spilled so a garden like that could exist.

This article was originally published in The Seattle Times.

FAQs

What does Issi and Nisei mean?

Nisei is a Japanese term that translates as "second generation" and refers to ethnically Japanese children born in a new country to Japanese-born immigrants. Issi is a Japanese term for Japanese immigrants to a new country.

Where did most Nisei fight in World War 2?

In 1940 about 5,000 Nisei were drafted into the US Army and comprised a large portion of the Hawaii National Guard's 298th and 299th Regiments.

What defines a Japanese garden?

Three essential elements for a Japanese garden are stone, water, and plants. Many Japanese gardens include trees, waterfalls, ponds, fish, moss, rocks, paths and bridges. The purpose of the garden is to remind us of the beauty of nature.

You may also be interested in...

Where to See Rhododendrons in the Seattle Area

Some of the best places to see rhododendrons are in or near Seattle Southside.